Emission and Absorption Spectra, Photon Energy, and Spectral Applications

- When standing in a pitch-dark room, you hold a glowing tube of gas in one hand and a prism in the other.

- As you shine the gas's light through the prism, a series of colorful lines appears on the wall.

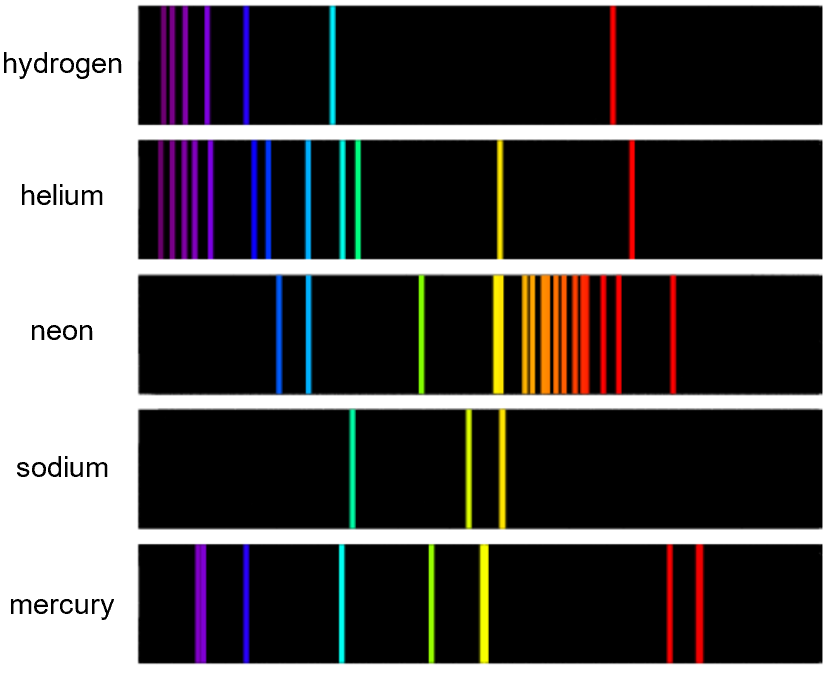

- These lines aren't random, they represent the unique "fingerprint" of the gas.

What you’re seeing is an emission spectrum, which shows how energy exists in discrete levels in an atom

Light Emission: Electrons Transitioning to Lower Energy Levels

- Think about a hydrogen atom: it consists of a single electron orbiting a positively charged nucleus (a proton).

- Within the atom, the electron can only exist in specific energy levels, which are quantized.

- This means the electron cannot possess an arbitrary amount of energy, it must "choose" from a discrete set of allowed energy levels.

How Does Light Emerge?

When an electron transitions from a higher energy level to a lower one, it releases energy in the form of light.

This light is emitted as a photon.

Photon

A photon is a tiny particle that comprises waves of electromagnetic radiation.

- Photon's energy determined by the equation: $$E = hf$$ where:

- $E$ is the energy of the photon,

- $h = 6.63 \times 10^{-34} \, \text{J·s}$ is Planck’s constant,

- $f$ is the frequency of the emitted light.

- The frequency $f$ determines the color of the light.

- Since the energy levels in an atom are fixed, the emitted light has specific, predictable wavelengths.

- When passed through a prism or diffraction grating, this light separates into distinct lines, forming the emission spectrum.

Emission spectrum

The emission spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation emitted due to an atom or molecule transitioning from a high energy state to a lower energy state.

- Consider an electron in a hydrogen atom transitioning from the $n = 3$ energy level $-1.51 \, \text{eV})$ to the $n = 2$ energy level $-3.40 \, \text{eV}$.

- The energy of the emitted photon is: $$\Delta E = E_{n=3} - E_{n=2} = -1.51 \, \text{eV} - (-3.40 \, \text{eV}) = 1.89 \, \text{eV}$$

- Convert this energy to joules $1 \, \text{eV} = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J})): $$\Delta E = 1.89 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19} = 3.024 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}$$

- The wavelength (\lambda) of the emitted photon is calculated using: $$\lambda = \frac{hc}{\Delta E} = \frac{6.63 \times 10^{-34} \times 3.0 \times 10^8}{3.024 \times 10^{-19}} = 6.58 \times 10^{-7} \, \text{m}$$

- This wavelength corresponds to red light, visible in the hydrogen emission spectrum.

Light Absorption: Electrons Transitioning to Higher Energy Levels

- Now, consider shining white light (which contains all colors) through a gas.

- As the light passes through, certain wavelengths are absorbed by the gas, leaving dark lines in the transmitted light.

- These dark lines form the absorption spectrum.

Absorption spectrum

Absorption spectrum is the range of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation readily absorbed by a substance by virtue of its chemical composition.

How Does Absorption Work?

- For an electron to move from a lower energy level to a higher one, it must absorb a photon with energy exactly equal to the difference between the two levels.

- Photons with the "wrong" energy simply pass through the gas without being absorbed.

Interestingly, the absorption spectrum of an element is the inverse of its emission spectrum: the dark lines in the absorption spectrum occur at the same wavelengths as the bright lines in the emission spectrum.

- If a hydrogen atom in its ground state $n = 1$ absorbs a photon with energy $10.2 \, \text{eV}$, the electron transitions to the $n = 2$ level.

- Photons with this energy are absorbed, leaving a dark line at the corresponding wavelength in the absorption spectrum.

- A common misconception is that absorbed photons "disappear."

- In reality, absorbed photons are re-emitted, but in random directions.

- This is why dark lines appear in the absorption spectrum when observing the light along its original path.

Photon Energy and Its Relation to Frequency

- The energy of a photon is directly proportional to its frequency, as described by $E = hf$.

- Using the relationship between frequency $f$, wavelength $\lambda$, and the speed of light $c$, we can rewrite this as: $$E = \frac{hc}{\lambda}$$ where:

- $c = 3.0 \times 10^8 \, \text{m s}^{-1}$ is the speed of light,

- $\lambda$ is the wavelength of the photon.

This equation highlights the inverse relationship between energy and wavelength:

- photons with shorter wavelengths (e.g., ultraviolet light) have higher energy,

- while those with longer wavelengths (e.g., infrared light) have lower energy.

- When solving problems involving photon energy, ensure your units are consistent.

- For example, convert electron volts (eV) to joules (J) when using Planck’s constant in SI units.

Applications of Spectroscopy: Determining Chemical Composition

- One of the most powerful uses of emission and absorption spectra is identifying the chemical composition of substances.

- Each element has a unique set of energy levels, meaning its spectral lines act as a "fingerprint" for identification.

Spectroscopy in Action

- Astronomy:

- Scientists can identify the elements in a star’s atmosphere by analyzing the absorption spectra of starlight.

- Forensics and Chemistry:

- Spectroscopy helps identify unknown substances in forensic investigations and chemical analysis.

- Environmental Science:

- Emission spectra are used to monitor pollutants in the atmosphere by detecting specific gases.

The discovery of hydrogen and helium in distant galaxies provided key evidence for the Big Bang theory.

- What is the relationship between photon energy and wavelength?

- How do emission and absorption spectra differ, and why do they occur at the same wavelengths?

- Why are spectral lines unique to each element, and how can they be used to identify unknown substances?